we're off to see the wizard...

March 18, 2010

Actually, we just got back. Jeff Lemire, Matt Kindt and myself road-tripped up to Seattle this last weekend for the Emerald City Con, and let me tell ya folks... after attending this show since the very first event, this was one hella rocking show. Great time all around. Hopefully i'll get some pics uploaded to our Flickr account soon. I'll let you know if i do.

Meanwhile, here's the second post by friend-of-Top Shelf, Trevor Dodge. Good stuff!

•••••••••••••••••••••••••••••

Picturebook Pedagogy #2: [Mc-]Clouding the Issue

A couple of weeks ago, an exceptionally bright and talented illustration student (we’ll call him “Jim” because, well, that’s his name) turned in his written response to Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, in which he complained that he has had the book either directly assigned or namedropped to him in five other classes at the same institution. UC’s ubiquity isn’t the problem, he argued, so much as the institutional stutter that sets in i/r/t this particular text with colleges and universities fortunate enough to even have courses in comics. Why, Jim asks, does his school find itself repeating itself so much when it comes to McCloud’s book?

A couple of weeks ago, an exceptionally bright and talented illustration student (we’ll call him “Jim” because, well, that’s his name) turned in his written response to Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, in which he complained that he has had the book either directly assigned or namedropped to him in five other classes at the same institution. UC’s ubiquity isn’t the problem, he argued, so much as the institutional stutter that sets in i/r/t this particular text with colleges and universities fortunate enough to even have courses in comics. Why, Jim asks, does his school find itself repeating itself so much when it comes to McCloud’s book?

Having first appeared in 1993 from Denis Kitchen’s little-press-that-could, UC is a book approaching two uninterrupted decades in print and showing little indication that it is slowing down. It’s been translated into 16 different languages, is now published by a corporation owned by Rupert Murdoch, and consistently salesranks among the top books on Amazon.com (on March 9, UC’s salesrank was around 1,800; the softcover trade edition of Alan Moore and David Lloyd’s V for Vendetta, by comparison, was hovering just below 3,800, Frank Miller’s Dark Knight Returns just above 2,700, and the “Preludes & Nocturnes” arc of Neil Gaiman’s run on Sandman right around 4,000. Did I forget to mention that Amazon indexed well over 4,000,000 titles last year? I’ll just keep chirping here while you do that math…). Do a quick websearch for the book’s title right now and you’ll usually discover within the first 10 links that UC is commonplace on BitTorrent networks, and has been for the better part of five years.

Having first appeared in 1993 from Denis Kitchen’s little-press-that-could, UC is a book approaching two uninterrupted decades in print and showing little indication that it is slowing down. It’s been translated into 16 different languages, is now published by a corporation owned by Rupert Murdoch, and consistently salesranks among the top books on Amazon.com (on March 9, UC’s salesrank was around 1,800; the softcover trade edition of Alan Moore and David Lloyd’s V for Vendetta, by comparison, was hovering just below 3,800, Frank Miller’s Dark Knight Returns just above 2,700, and the “Preludes & Nocturnes” arc of Neil Gaiman’s run on Sandman right around 4,000. Did I forget to mention that Amazon indexed well over 4,000,000 titles last year? I’ll just keep chirping here while you do that math…). Do a quick websearch for the book’s title right now and you’ll usually discover within the first 10 links that UC is commonplace on BitTorrent networks, and has been for the better part of five years.

In short, it’s simply not enough these days to say that McCloud has become an important voice for comics. We’re well past that point. It’s a lot closer to the mark to say that McCloud has become the voice for comics, at least as far as academia here in the United States is concerned. It’s hard to imagine discovering a fine arts, graphic design and/or humanities department anywhere in this country that hasn’t seen the title of that book appear on at least one instructor’s syllabus over the past fifteen years.

Quick tangent, I promise: when I was taking my undergraduate literature courses, I had much the same reaction to F. Scott Fitzgerald as Jim had to Scott McCloud (it must be something about that “Scott” name, right?). Regarding The Great Gatsby: yeah, I understand “great” isn’t just part of the title, it largely enacts a set of cultural expectations that come about as close to the word “mandate” as the U.S. intelligentsia-literati are comfortable with; yeah, I understand that when we use the phrase “Great American Novel” to describe another book, it’s almost always this one we’re really talking about. See, I read Fitzgerald’s book, and I was largely non-plussed by it, but I also went into reading it with the culture largely having made up its mind about this particular expression long before I came to it (c.f. J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye for similar meh-ness; as I type this, my discourse community is currently mourning the passing of Mr. Salinger, who, in his post-Catcher time with us here on earth, made the lives of a lot of fawning literature scholars insanely, litigiously difficult with an army of lawyers rivaled only by the likes of Steve Jobs and C. Montgomery Burns). UC apparently for a new generation of students is now such a text.

Quick tangent, I promise: when I was taking my undergraduate literature courses, I had much the same reaction to F. Scott Fitzgerald as Jim had to Scott McCloud (it must be something about that “Scott” name, right?). Regarding The Great Gatsby: yeah, I understand “great” isn’t just part of the title, it largely enacts a set of cultural expectations that come about as close to the word “mandate” as the U.S. intelligentsia-literati are comfortable with; yeah, I understand that when we use the phrase “Great American Novel” to describe another book, it’s almost always this one we’re really talking about. See, I read Fitzgerald’s book, and I was largely non-plussed by it, but I also went into reading it with the culture largely having made up its mind about this particular expression long before I came to it (c.f. J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye for similar meh-ness; as I type this, my discourse community is currently mourning the passing of Mr. Salinger, who, in his post-Catcher time with us here on earth, made the lives of a lot of fawning literature scholars insanely, litigiously difficult with an army of lawyers rivaled only by the likes of Steve Jobs and C. Montgomery Burns). UC apparently for a new generation of students is now such a text.

As McCloud’s text rages on to its umpteenth printing and into its further entrenchment in the bunkers of academia, it’s probably important to point out something McCloud himself addresses early on in UC. And that something is this: McCloud owes a great deal to Will Eisner, whose work in both the practice and theory of comics is absolutely essential to the medium’s growth in the United States. Now, of course, I’m not telling subscribers to the RSS feed for this fair blog anything they don’t know (ya’ll are a clever and well-read bunch!); one only needs to contemplate the meteoric and magnificent career of Michael Chabon to see how important and influential Eisner was to an entire generation of artists after him (not just comics creators, either; Chabon might have won his Pulitzer in the post-Maus era, but it was awarded for a superb sprawl of sentences and paragraphs b/k/a The Adventures of Kavalier and Clay).

See, the reason I repeat what’s already been said by plenty of others on this Eisner→McCloud tip is that UC is probably already the first academic explication of the medium U.S. college students are exposed to, and could very well be the only theoretical approach to comics most students will read (and let’s make sure we distinguish between “most” and “serious” when it comes to students, because serious students like Jim are sure to push far into Eisner’s critical oeuvre, as well as into excellent contemporary criticism by the likes of Charles Hatfield, Danny Fingeroth, and the late Lillian S. Robinson). Those of us who still have a Kitchen Sink printing may not be thinking about this—let alone worried about it yet—but if what Jim is saying hits even remotely close to the mark, Understanding Comics has become this generation’s Ways of Seeing (or The Medium is the Massage before that). In essence, as his generation’s John Berger, Scott McCloud is—for the lack of a better term—The Man. (Hell, even Eisner himself defers to McCloud in these regards, blurbing UC as a “landmark dissection and intellectual consideration,” insisting that “everyone…anyone interested in this literary form must read it. Every school teacher should have one.” To my student Jim’s point: we’re close to the point—if not already past it—where Eisner’s phrase “should have” is an anachronism, and needs replaced with “already has.”)

See, the reason I repeat what’s already been said by plenty of others on this Eisner→McCloud tip is that UC is probably already the first academic explication of the medium U.S. college students are exposed to, and could very well be the only theoretical approach to comics most students will read (and let’s make sure we distinguish between “most” and “serious” when it comes to students, because serious students like Jim are sure to push far into Eisner’s critical oeuvre, as well as into excellent contemporary criticism by the likes of Charles Hatfield, Danny Fingeroth, and the late Lillian S. Robinson). Those of us who still have a Kitchen Sink printing may not be thinking about this—let alone worried about it yet—but if what Jim is saying hits even remotely close to the mark, Understanding Comics has become this generation’s Ways of Seeing (or The Medium is the Massage before that). In essence, as his generation’s John Berger, Scott McCloud is—for the lack of a better term—The Man. (Hell, even Eisner himself defers to McCloud in these regards, blurbing UC as a “landmark dissection and intellectual consideration,” insisting that “everyone…anyone interested in this literary form must read it. Every school teacher should have one.” To my student Jim’s point: we’re close to the point—if not already past it—where Eisner’s phrase “should have” is an anachronism, and needs replaced with “already has.”)

This poses a particularly itchy problem for me because, well, I like Scott McCloud, and a big part of that has a lot to do with him helping me discover a way to talk about comics beyond the sophomoric blathering always inherent to the “Who Would Win In A Fight Of ___ Vs. ____?” postulation that, if you spend enough time in comic book shops (guilty) or in courses on comics (ditto) are far too familiar and usually endowed with a deadpan philosophical delivery that is both unmistakeable and desperate. I’ve taught McCloud’s book, either in pieces or in its entirety, for the better part of a decade, and Jim’s grumblings now have me seriously thinking about something I frankly hadn’t given much thought to and probably should have.

![]() So here then, fair Top Shelfers, here are my Top Ten Reasons To Continue Teaching Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics. And because I’ve always been a Team Conan guy, we’re doing it Letterman style:

So here then, fair Top Shelfers, here are my Top Ten Reasons To Continue Teaching Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics. And because I’ve always been a Team Conan guy, we’re doing it Letterman style:

10) Scott McCloud is genuinely a genuine human being. I know this because I had the pleasure of meeting him when he taught a week-long workshop at PNCA’s inaugural Graphic Novel Intensive in Portland in 2007. While here, he also gave his amazing Keynote presentation (I’d call it a Powerpoint show but I refuse to degrade it in any way, especially by using the term “Powerpoint”) in the Weiden + Kennedy forum, the props for which were his own adorable little family. His wife and daughters were touring the country with him for the then-recently released Making Comics, and I can tell you it is quite literally impossible for me to be objective about McCloud and his work simply because his youngest daughter back then could melt diamonds with her intelligence and bashfulness. In short, McCloud has made comics not only his life, but that of his entire family. That’s quite a commitment.

9) Twitter. I’m being serious here. This really matters. Now, true: McCloud hasn’t yet developed the ninja speed of Warren Ellis or Brian Michael Bendis when it comes to rapidfire updates on Twitter. However, he’s a frequent enough flier on the failwhale airship to warrant mentioning, and his contributions are typically comics topical, looping back into his source texts and extending/exampling their arguments. On large, traditional academic work tends to be a snapshot of the time, place and circumstances during which the research was conducted and final analysis made, and is usually already outdated by the time said work appears in front of another pair of eyes besides the scholar and her editors. McCloud’s presence on the web is both pervasive and long-standing, and he uses his online avatar much in the same way he does his cartoon self in his comics. That is, he extends the conversation through a variety of media; just take a look at his TED presentation from a few years back, when things like myspace, blogs and Facebook were mostly in their infancy, and Twitter was but a sparkle in the collective eyes of Jack Dorsey, Evan Williams and Biz Stone.

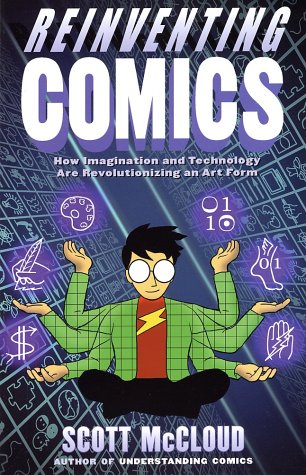

9) Twitter. I’m being serious here. This really matters. Now, true: McCloud hasn’t yet developed the ninja speed of Warren Ellis or Brian Michael Bendis when it comes to rapidfire updates on Twitter. However, he’s a frequent enough flier on the failwhale airship to warrant mentioning, and his contributions are typically comics topical, looping back into his source texts and extending/exampling their arguments. On large, traditional academic work tends to be a snapshot of the time, place and circumstances during which the research was conducted and final analysis made, and is usually already outdated by the time said work appears in front of another pair of eyes besides the scholar and her editors. McCloud’s presence on the web is both pervasive and long-standing, and he uses his online avatar much in the same way he does his cartoon self in his comics. That is, he extends the conversation through a variety of media; just take a look at his TED presentation from a few years back, when things like myspace, blogs and Facebook were mostly in their infancy, and Twitter was but a sparkle in the collective eyes of Jack Dorsey, Evan Williams and Biz Stone. 8) Don’t say he didn’t tell you so. McCloud has long championed The Internet and World Wide Web as offering comics an exciting opportunity to multiply and mutate, and he is among those least surprised by the rise of webcomics as not only worthwhile creative expressions in and of themselves, but social hubs for creators and readers to come together in ways a previous generation of comics artists could only dream. When McCloud’s sequel to UC—Reinventing Comics—was published in all-too-appropriate year of Y2K, many in the comics community snorted at some of its predictions and prognostications for how a traditionally print-bound medium like comics would not just survive in the digital age, but thrive. If the names Penny Arcade, Dinosaur Comics, Perry Bible Fellowship, Get Your War On and Top Shelf 2.0 mean anything at all to you…well, you get the idea.

8) Don’t say he didn’t tell you so. McCloud has long championed The Internet and World Wide Web as offering comics an exciting opportunity to multiply and mutate, and he is among those least surprised by the rise of webcomics as not only worthwhile creative expressions in and of themselves, but social hubs for creators and readers to come together in ways a previous generation of comics artists could only dream. When McCloud’s sequel to UC—Reinventing Comics—was published in all-too-appropriate year of Y2K, many in the comics community snorted at some of its predictions and prognostications for how a traditionally print-bound medium like comics would not just survive in the digital age, but thrive. If the names Penny Arcade, Dinosaur Comics, Perry Bible Fellowship, Get Your War On and Top Shelf 2.0 mean anything at all to you…well, you get the idea.

7) Visual rhetoric. McCloud understands the power of images, and uses them to great effect in his theoretical work. You know the maxim “a picture is worth a thousand words”? Whoever coined that phrase way back when surely also invented a time machine, transported herself to 1993, picked up a copy of Understanding Comics, cracked it open to McCloud’s enaction/definition of the picture plane, and then invented another time machine to go back and plant that magical maxim in our cultural memories. Go ahead and try to explain that concept using nothing but sentences and paragraphs. I double-dog dare you.

6) Structuralism is still useful despite what happened during the Theory Wars in the 1970s and 1980s. Look no further than David Mazzucchelli’s brilliant Asterios Polyp for confirmation that not only has Structuralism survived into the second decade of the 21st century, but has shown itself cuddlingly capable of telling an endearing love story. (None of us could have seen that coming.) One of McCloud’s agenda items with UC is to apply semantic/semiotic techniques to a medium that is already largely/inherently semiotic to begin with. Eisner, of course, understood this, but his theoretical explorations of the medium serve and read more like shop talk (no coincidence, then, that he so often used that very phrase in his studies) than does McCloud’s full-blown structuralist analysis.

6) Structuralism is still useful despite what happened during the Theory Wars in the 1970s and 1980s. Look no further than David Mazzucchelli’s brilliant Asterios Polyp for confirmation that not only has Structuralism survived into the second decade of the 21st century, but has shown itself cuddlingly capable of telling an endearing love story. (None of us could have seen that coming.) One of McCloud’s agenda items with UC is to apply semantic/semiotic techniques to a medium that is already largely/inherently semiotic to begin with. Eisner, of course, understood this, but his theoretical explorations of the medium serve and read more like shop talk (no coincidence, then, that he so often used that very phrase in his studies) than does McCloud’s full-blown structuralist analysis.

5) Have I said what a swell guy Scott McCloud is already? (Sorry.)

4) Where Eisner was one of the first to tap the educational power of comics, for all intents and purposes, McCloud has largely perfected it. It never gets old watching students’ faces light up when they talk about McCloud’s book for the first time. Because for them, the realization that they are breathing life into a functional medium is very very real. The medium’s viability requires their active participation to construct meaning, that it needs them in ways that prose, film and even a so-called “interactive” medium like videogames do not. Consider for a moment that as you’re reading this, there are literally thousands of film screenings happening right now that don’t require your presence. Eisner taught us the democratic nature of comics through the wide range of texts his studio produced; McCloud enacts this by turning on a light inside his readers that only seems to burn brighter going forward.

3) Pleased to meet you. For many of my students, UC is not only the first textbook they read in my classes, but it is quite literally the first major comics work of any heft or substance they have ever read. (Ever as in, you know, ever?) When I started teaching full courses in comics, I’d say close to 90% of the students were already familiar with the medium and had read at least one trade collection or graphic novel. I’d peg that number closer to 50% these days; on the surface, someone might argue that this marks a decline in comics readership, but I really don’t see that from my vantage point. What I’m seeing is more and more students coming to class having heard about stuff going on in comics from other people and/or media experiences. In short, they are curious. And curiosity is a very good thing not only for pedagogical purposes, but also to breathe new life into the comics industry. My comics courses are easily the most diverse classes I teach (I also teach fiction writing, composition, lit theory and games studies) in terms of student ages, races, class, and gender, and a large number of those students are coming in largely just to see what the medium has to offer.

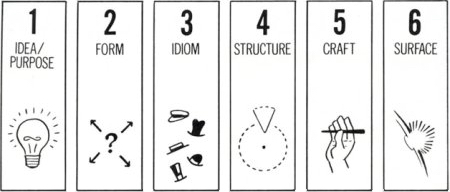

2) The Creative Process. McCloud dedicates an entire chapter to explicating “Six Steps” for artists. Over the years I’ve had a fair number of students howl about McCloud’s clinical vivisection of “the artistic process,” something they may largely inuit or even think of as a form of magic, and how confining/cold that particular part of the book can come across. But what tends to happen after the initial disgruntlement and bristling is always worthwhile: exploring, communicating and discovering how comics are part of rhetorical efforts that transcend not only genres but discrete media.

2) The Creative Process. McCloud dedicates an entire chapter to explicating “Six Steps” for artists. Over the years I’ve had a fair number of students howl about McCloud’s clinical vivisection of “the artistic process,” something they may largely inuit or even think of as a form of magic, and how confining/cold that particular part of the book can come across. But what tends to happen after the initial disgruntlement and bristling is always worthwhile: exploring, communicating and discovering how comics are part of rhetorical efforts that transcend not only genres but discrete media.

1) The Conversation. McCloud’s Understanding Comics has given us much to consider and argue about over the years, and those expressions matter. In the end, they are probably what matters most. After all, isn’t that why you’re here of all places on the World Wide Web, doing something as horribly low-tech as reading? Seriously, if you were all about the point-click-point-click, wouldn’t you really rather fiddle with Solitaire, Minesweeper or Bejeweled all day?